Episode 8:

Cannabis, Nature's Epigenetic Switches, Peptides and Healing Micronutrient Therapy

Importance of micronutrients is discussed. The lack of micro nutrients can lead to many diseases and inflammation. Some recommended essential micronutrients are Vitamin C, Amino Acid Lysine, trace elements, a part of green tea. They reduce inflammation.

A complete book,

"Victory Over Cancer" by

Dr. Mathias Rath, explains the cancer cure using micronutrients. It is available for on-line down load. And did I mention it's free?

(^_-)-☆ →

Victory Over Cancer

Food can be epigenetics. As stated in the earlier Episode, only 5% of cancer is genetically influenced. This means you can do a lot to avoid cancer by what you do, think and eat/drink. Our

lifestyle choices can majorly influence gene expressions.

Gerson Therapy

Although original therapy introduced by Dr. Max Gerson, M.D. might have been effective, in my family's own experience, years after his passing, didn't prove to be effective.

I think the main reason was that the severe unbalance of potassium and sodium intake. Juicing and all cooked down food didn't have any sodium. I hope the current therapy has corrected this major shortcomings. Please contact me, if you'd like to know more about this therapy.

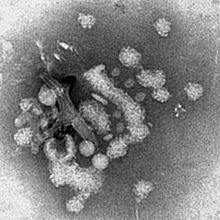

Hemp Oil is an oil extracted from the hemp plant. All plants in the Cannabis genus can produce the oil, but usually

only industrial hemp is used to make hemp oil. Industrial hemp is a hemp varietal which has been cultivated specifically for industrial production, and it

has a minimum of the psychoactive substances, most notably

THC. Hemp oil is typically almost

free of THC, and it has

no psychoactive properties.

Hemp Oil Benefits

The hemp oil has a number of health benefits and its products as well as its raw forms are used to provide many essential amino acids to the body. If the body is deprived of any of these amino acids there are serious problems like genetic mutations and cancer. Hemp oil cures cancer as the essential and non-essential amino acids are present in abundance in the oil and thus when hemp oil is regularly used by cancer patients, there are chances of cure.

Since Hemp oil is in the same Cannabis family as Marijuana, can smoking marijuana help fight

cancer? I don't think so.

I have a long-time 'medical' marijuana user who comes once in awhile. He always seem to be 'intoxicated' at some level. The recreational use of marijuana was legalized in Oregon recently. And another client of mine started to smoke marijuana. When I asked how he was doing, without knowing he started the use, he replied, "I'm happy." I guess it has some psychoactive properties (THC) in it, while the hemp oil doesn't. I'm not sure about the medicinal use of recreational smoking marijuana. I was informed that this 'legalization' was mainly to increase State's revenue in taxes. It always seems to be about money....

Being happy is better than being depressed, I supposed, but there are other ways to get happier than literally 'burning' your money on weeds. (^_-)-☆

Intermittent Fasting

We eat too much. If not too much, too often. Primary fuel for Cancer cells is glucose (sugar). Non cancer cells can use either glucose or fat as fuel. With the constant 'feeding' the body has little chance to use fat as energy since 'sugar' energy is easily accessible. Body stores excess sugar as Glycogen in muscles and liver. Aside from limiting processed sugar, you want to give your digestive system a rest at least 12 hours a day. Supply of glycogen lasts at least 12 hours. Don't eat at least 3~4 hours before bed time. And get enough sleep at night!

For diabetic people, the adequate fasting period maybe critical. Have your resting insulin level checked, not the resting blood sugar level. You want to keep the blood insulin level below 3.

Excessive energy, mainly derived from sugar, kills mitochondria (cells' energy production center), causes premature aging and creates free radicals.

Ketogenic Diet (along with Intermittent Fasting)

A ketogenic diet is one that is high in protein and healthy fats, but low enough in carbohydrates to trigger the condition of ketosis. This diet was originally developed to treat epilepsy, but is also currently used for weight loss and managing Type 2 diabetes.

There is some evidence that following a ketogenic diet may help cancer treatment, according to a paper published

on Science Direct. It may

help slow tumor growth and prevent new tumors from forming.

Eliminate Omega 6 oil. It oxidizes too fast, which becomes cancer fuels and inflammatory.

Omega 6 oils: Corn, Sufflour, Sunflower, Peanut oil, Canola oil.

Instead, use: Avocado, Coconut oil, olive oil (in low temp. only), Nuts

Bon Appetit!